An Exercise in Middle Woodland Geometry IV

- Bill Beaver

- Sep 10, 2024

- 66 min read

Updated: Jul 13, 2025

Newark Earthworks 1836 by Charles Whittlesey [Squier & Davis 1847]

Part IV - Newark, the Core, and Beyond

Newark Earthworks 2005 [Romain 2007]

"To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering." [Aldo Leopold]

For thousands of years before European contact, the peoples of eastern North America have lived along the banks of the region's many rivers. They built structures of wood and other plant materials, lost to the wet climate. They also built by modifying the landscape. They moved dirt around. Mostly they created mounds, to intern the dead, to decommission great wooden houses where the dead were often processed, or as raised foundations, platforms for other structures. At different points in time, they built both large and small earthen enclosures. Archaeologists chunk out long periods of the past and give them names. The period between approximately 100 B.C.E. and 700 C.E. has been named 'Middle Woodland.' This period includes the birth of local agriculture and the gradual expansion of Mesoamerican 'three sisters' agriculture. The period also included the cultural dominance of what is now called 'The Hopewell Interaction Sphere.' This is a set of mortuary and religious practices; the extraction, manufacture, and trade of many exotic goods; and the construction of large earthworks, many geometric in shape, mostly circles and squares. These are concentrated in the Scioto River Valley in southern Ohio, called the 'Core', but can be found in other Eastern North America locations.

The Colonial Period in North America has led to the deliberate attempted erasure and incredible resilience of its native peoples. This is true for their earthen structures. It is telling that for some structures, the only known information comes from 19th-century maps. This has changed in the last thirty years with new technologies and a growing concerted effort to save them. Who would have known that the earthworks would put a lasting magnetic signature upon the land, a signature resistant to the all-leveling plow? They still exist, alive, with stories to tell for all who listen.

Earthworks as an artifact

An artifact is any object made by a human. In archaeology, portable objects made by humans are called 'artifacts,' and non-portable objects made by humans are called 'features.' Sometimes a third term is used, 'structures.' [Center for Archaeological Studies 2019] Whatever the name, all of these objects are in essence artifacts, they have properties that are both measurable and stylistic and can be placed in a spatial context. With the advent of digital maps and 3D reconstruction, the difference between portable and non-portable artifacts becomes mute, everything is now potentially portable.

Artifacts are described by sets of labels and numbers which I will call 'attributes.' Among these attributes are 'types' or 'categories,' an attempt to clump artifacts into groups. A thousand ceramic sherds might be from 11 different pots of three distinct styles. Some believe that categorization is a major component of intelligence [Adami 2024] and humans excel at it to the extent of finding categories where none exist. Categorization has a computational component called 'clustering.' [Tversky 1977] Cluster analysis can be an exploratory process of finding new categories. [Oyewole & Thopil 2023] Computational clustering points out possibilities, it is up to the researcher to interpret the results. Also, there are any number of ways to define or measure an artifact, what is important depends on the research question, the theoretical framework from which the question is asked, and the usefulness of the definition or measure. [Read 2007]

In the late 1970s with the beginning of personal computers, multivariate statistics, statistics with more than one variable, became possible. Today much statistical analysis is assumed to be multivariate. Intrasite analysis is a method of looking at the spatial patterns portable artifacts leave on a site and how these relate to the features of a site. Where things are dropped and what things are dropped leave clues as to why they were dropped. A Holy Grail of science has been the attempt to find universal constants that define a process. Chris Carr has attempted to define an analysis using a ‘coefficient of polythetic association.‘ [Carr 1984] Polythetic is an anthropological term of categorization. It is best defined by an analogy attributed to the philosopher Wittgenstein as ‘family resemblance.’ [Needham 1975] In 1991 Hans Peter Blankhorn tested over twenty different intrasite analytical methods against site data collected by L. R. Binford. Unfortunately, Carr’s method didn’t make the first cut. [Blankholm 1991]

The reason for this failure has only been recently realized. Intratsite spatial patterns can be abstracted as a spatial network and network theory has found hundreds of coefficients, only a few of any use, and none universal. [Barthelemy 2022] This problem with coefficients seems to be a feature of a complex process. One needs to speak instead of parameters. What are the important parameters and what is their range of values?

I am of the opinion that the study of non-portable artifacts or features, is still in its infancy but please prove me wrong. That said I have found examples that I include at various places within this article and mark with a symbol:

The examples are below the symbol as follows:

I am looking at the geometric earthworks in particular. At the moment this is just an outline, not an analysis, whether these show any patterns is an open question. Statistical power is also a problem, one needs enough data to get results. A possible solution is Monte Carlo simulation. [Hively and Horn 2006] A random set of relationships or measurements, a statistical model, is generated and compared against the real data. If the probability of the original measurements falling within the random set is low then the original measurements have some meaning within the model.

The earthworks at one level can be decomposed into a set of measurements and a set of relationships. These relationships can be topological or based on mathematical assumptions about the measurements. This combined set is just one element in describing an earthwork site as an artifact. These encoded descriptions can be compared to see patterns and clusters.

The surveyor James Marshall wrote this in 1969:

"Equal concern has not been directed to the analysis of archaeological structures, or 'features' as they are most often called. With rare exception, features are given brief and often general treatment in archaeological reports. They are classified into major functional classes, e.g., storage pit, hearth, house, or tomb, with little interest taken to elaborate the formal characteristics of these features. If formal attributes were recorded, a study of their correlations might enable the investigator to recognize different design or 'style' types within any given functional class of features. It might also lead to more refined functional distinctions." [Marshall 1969]

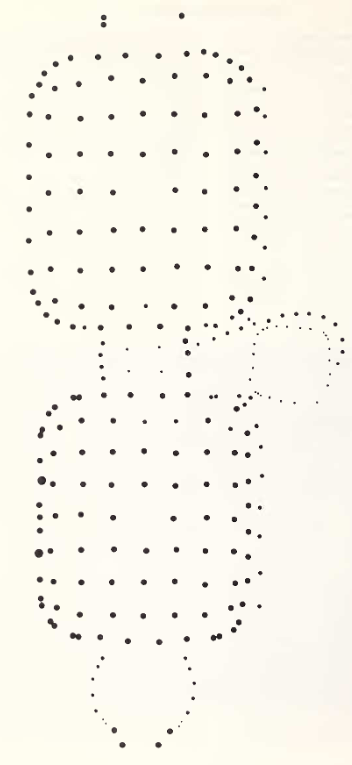

In his paper, Marshall asks, based on engineering principles, if any information can be obtained, about a Middle Woodland site called Apple Creek in Illinois and the remains of a structure called Pike House, Pike being the name of a local culture having Hopewell influence. All that remains of the structure are post holes, middens, and pits. Marshall takes three measures from the pits, depth, diameter, and the slope of the base, and calculates a resistance-strength index from each. This is a measure of the horizontal and vertical strength of the wooden poles that were placed in the holes. He creates rough categories to find which posts held up the structure. He concludes that this was a tent-like structure created for ease of assembly and disassembly as the site was only used for part of the year. He also talks about the geometry (shape) of the structure which he determines as not an ellipse. Today this shape would be called a squircle.

Pike House Apple Creek Site, Illinois [Marshall 1969, p. 167, fig. 1]

Marshall's paper was the last one published in a standard format as he became increasingly interested in the geometry of the earthworks and the geometric knowledge of the builders. In 1987 he published An Atlas of American Indian Geometry. in Ohio Archaeologist. [Marshall 1987] He published a table of his surveyed structures. In 1996 he published Towards a Definition of the Ohio Hopewell Core and Periphery Utilizing the Geometric Earthworks. [Marshall 1996] He attempted a classification of the sites by classifying them according to the amount of mathematical knowledge the builders needed to build them:

No Mathematical Knowledge - The earthworks were originally classified as 'forts,' but now are called 'hilltop enclosures.' Some known enclosures contain geometric elements, straight lines, curves, and the largest one, Fort Ancient, contains a circle of posts, a 'woodhenge,' that might have been the template of an earthwork. [Riodan 2020]

Basic Unit of Measurement - Marshall claims a unit of measure of 57 m. or 187'. If this unit is used as the side of a square, a second unit of measure, the diagonal of this square, is constructed.

Cryptographs - The idea is that by looking at a site as a whole, taking circles and/or parts of circles, squares and/or parts of squares, and drawing lines between their edges and centers, other geometric figures can be constructed. This is called Ad Quadratum for constructing squares and Ad Triangulum for triangles. These are terms for using proportions of geometric forms in architecture to analyze Gothic Cathedrals. Just like a circle can inscribe and circumscribe a square, another square rotated 45 degrees can inscribe and circumscribe this same square. The side and diagonal form a geometric progression. Inscribed and circumscribed circles can be added. Marshall constructed Ad Quadratum figures by connecting center points.

Cryptograph of the Liberty Township Works [Marshall 1996 p. 214]

Cryptographic Overlays - Two earthworks sites overlay each other after some rotation or transformation.

Enlargement of the High Banks Works placed over a cryptograph of the Baum Works [Marshall 1996 p. 217]

The Concept of Pi - The relationship between the double circles found at many earthworks, one inside the other like the works at Circleville Ohio. The outer circle inscribes a square of 9 units on a side and 81 units in area. If one constructs an octagon around the outer circle, the square grid can be used to find the octagon's area which is 63 units. This gives an estimated area of the larger circle. A square inside the octagon is 8 units on a side. It has an area of 64 units, another estimate of the area of the larger circle. Using these two estimates a range of values around pi can be calculated. The actual earthwork construction of the inner circle uses 1/2 the side of the original square as a radius. [Geometry]

The idea that these categories form an ordered progression and can be used for casual inference is weak. Still, I would like to comment on each of the categories:

No Mathematical Knowledge - Robert Riordan has documented eight hilltop enclosures in Ohio. [Riordan 1996] I have found an obscure mention that there are around twenty in Kentucky but nothing about them. [Pollack 2008] A geometric shape has been found at Fort Ancient within the hilltop enclosure. [Riodan 2020] The builders did not have the luxury of a flat landscape so they created one themselves, an extraordinary feat that required intensive skill and labor. The earthworks also show evidence of reuse by later cultures. What they did within these enclosures is still an open question, perhaps this was where the mathematical knowledge was created.

Basic Unit of Measurement - A controversial claim that can be tested. [Measure]

Cryptographs and Cryptographic Overlays - Without either a computational means to find center points or an error model of the surveys cryptographs are just an interesting exercise. [Geometry] I also believe that the cryptographs created by the relationship between the earthwork and its landscape (including the sky) are much more useful. [Landscape]

His 1987 table doesn't specifically use all these categories. I copied all this data to digital form, corrected misspellings, broken combined data into columns, and added new columns. One difficulty I have had is names. Marshall's name for the site is not always the current name of the site. I find some of his categories and conclusions iffy, but the raw data is important. In some cases, he is the only survey of a site since before the early 20th century. Some of the sites he surveyed now have LDAR or geophysical data. Thus the accuracy of his survey can be quantified. All his surveys and notes currently reside at the Ohio History Connection in Columbus, Ohio. [James Marshall Collection. Ohio History Connection]

In the same Chillicothe Conference volume that contained Marshall's article, William Romain published Hopewellian Geometry: Forms at the Intersection of Time and Eternity. [Romain 1996] He uses the Ad Quadratum construction to examine the geometric relationships between sites. He does not find any useful ordering. I have reservations about Ad Quadratum but his data is useful. This is also the first place I see mention of the area and perimeter equality between circles and squares, specifically at Newark.

In addition, the Chillicothe Conference volume contains an article by A. Martin Byers: Social Structure and the Pragmatic Meaning of Material Culture: Ohio Hopewell as Ecclesiastic Communal Cult. [Byers 1996] Byers proposes a coding scheme to describe within-site relationships. This is more accurately coded as a relational graph. This was the theme of his doctoral thesis in 1987. [Byers 1987] In 2005 Byers published a book similarly themed. [Byers 2005] As of this writing I have not been able to obtain the book or doctoral dissertation.

Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio is an example of an ‘effigy mound’, a mound built in the shape of an animal or a specific abstract symbol. Ohio has two other known earthen effigy mounds: the Alligator Mound (now considered a mythical creature called a ‘water panther’) and the Tarlton Cross. Tarlton Cross is similar to a much larger cross at Casa Grandes in Northern Mexico. Other serpent mounds exist in North America, one in Louisiana and the other in southwestern Ontario near the town of Peterborough. This is not a continuous earthwork but a series of mounds that form a sinuous shape, perhaps not a serpent at all. Eagle Mound at the center of the Great Circle at Newark was once typed as an effigy mound but it now considered to be taking on the shape of the structure that once stood there which was burned and mounded over. There is a great concentration of effigy mounds in Southern Wisconsin. There are stone serpent effigy mounds in Georgia, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Warren County, Ohio. [Sanders 1991] For the most part, effigy mounds are considered a later expression of mound building, Late Woodland or Mississippian although the Peterborough mounds have been dated as Middle Woodland.

Serpent Mound is by far the most famous with its great size and beautiful artistic form. The site has been used for a long time with an Early Woodland (Adena) mound and a Late Woodland (Fort Ancient) village nearby. During the late 1800s Fredrick R. Putman purchased the land for a park and ‘repaired’ the effigy. There is considerable controversy over who built the effigy, the Adena culture or a later Mississippian Fort Ancient culture. Radiocarbon dates from organic residue in the soil give an Adena construction. Dates from charcoal pieces give a Fort Ancient date. Both William Romain [Romain et al. 2017] and Brad Lepper [Lepper et al. 2022] use artifact snake iconography to argue Adena vs Mississippian. In addition, Lepper uses an older map of the effigy to give a specific interpretation and link this interpretation to ethnographic data and rock art found in Missouri.

When I look at maps I can see that whoever designed these geometric enclosures was fascinated with the equivalences between a circle and a square. Of course, only a few people then saw the geometries, from a hill or a temporary sketch, the rest experienced the enclosures differently, inside as a controlled landscape. In their artwork, in their portable artifacts, I don't see this fascination. Their art is very naturalistic. They do use symmetry. Here are a few things I've found in collections:

Stone rings from Hopewell Mound Group. The inner part of the ring is thinner and it looks like it has two parts, an inner and and outer like the ditches inside some circular enclosures. [Ohio History Connection Stone Rings]

A circular copper cutout with crossed perpendicular lines inside. [Ohio History Connection Copper Cut-out]

Fragments of an older (Adena?) split-cane mats used as a mortuary cover found in Kentucky with clear square patterning. [Marshall 1984]

The copper earspools are circular rings that became larger over time and the inner housing was created with a sharper angle giving better contrast between the center and the outer ring. They were either red or white. They were designed for visibility and visibility at a distance. [Ruhl & Seeman 1998] There is a figurine of a woman wearing ear spools with at least one side of her head shaved. [Ruggeri 2024] I also found a male figurine from Turner with the whole of his head shaved short. [Ohio History Connection Turner Mound pottery figure]

The tetrapod jars. If one looks directly inside would one see a circle with the four corners of a square inscribed? [Ohio History Connection Hopewell pottery vessel]

One stylistic element does connect with the portable art. Color and contrasting colors in the soil of the earthworks. [Charles 2012]

Warren DeBoer bases his insights on work he did at ceremonial sites at Esmeraldas, Ecuador. [DeBoer 1997] He is referencing A. Martin Byers original doctoral work. He is looking at relationships within and between the large geometric earthworks within the Ohio Core. [Byers 1987] These can be two-part, three-part and even four-part. One is the relationship between the circle and the square. He sees the square as representing winter and the circle summer. He mentions that at Seip, the large circle is dark and the square is red, the first mention that I've found of different colors between the geometric forms. He also relates the different animals found on effigy pipes to relationships between earth, sky and water. DeBoer's article in a book edited by A. Martin Byers [Byers 2010] is an attempt at a seriation using the orientations of Ohio Core earthworks with respect to each other. This is a third type of orientation, the other two being astronomical and landscape. DeBoer's figures and maps are complex and unfortunately the pdf copy I have does not reproduce them very well. In neither of his articles does he mention ditches or water features. [DeBoer 2010]

Newark

“These facts suggest that the Newark Earthworks can be viewed not merely as arcane symbols built upon the landscape, but as a gigantic machine or factory in which energies from the three levels of the Eastern Woodland Indian’s cosmos – the Upper World of the sky, the watery Underworld, and the Middle World of soil and stone – were drawn together and circulated through conduits of ritual to accomplish some sacred purpose. Perhaps they were the equivalent of our giant superconducting supercolliders: monumental machinery for unleashing powerful cosmic forces." [Lepper 2004]

The upper Rio Grande Valley from Santa Fe north to Taos into Colorado has been called 'The American Holy Land.' The reasons for this are the low Anglo population, the resilience of the Pueblo peoples, and the assimilation and protection of sacred sites by the Spanish Catholic church. Another American Holy Land exists in central Ohio, but the removal of all native peoples by 1850, the building of towns, roads, canals, railroads, and the plow have all but erased it. The colonial history of Newark earthworks, the attempts to save it, up to the present designation as a proposed World Heritage Site is a story for another time. Newark has been called 'a distressed cultural site' [Johnson 2016] meaning World Heritage status could be important for saving it. Brad Lepper relates that archaeologists have neglected Newark because no human remains have been found within the main structures. Newark has a separate mortuary enclosure containing mounds that have been flattened and built over. [Lepper 2016]

At over 4 square miles, Newark Earthworks is North America's largest neolithic geometric structure, perhaps in the world. The actual extent is an issue as the earliest map is considered inaccurate. [Squier & Davis 1847] Additional maps show other geometric enclosures but lack some of the details of the first.

James and Charles Salisbury's map of Newark Earthworks. Perhaps the most accurate available [Salisbury & Salisbury 1862]

Newark consists of at least 7 enclosures connected by a series of linear and curved embankments some connecting and others enclosing the geometric forms. In addition, a ceremonial road heads south which may lead to the Chillicothe Core some 60 miles away. The enclosures are as follows:

Observatory Circle: This circle still exists and is currently part of the Mounds Country Club. Opposite the main entrance and extending outside of the main wall is a large mound called Observatory Mound.

Octagon: A rare geometric form, one of only two I can find in Ohio. This does conform to the template of many of the squares, eight pieces with open entranceways occluded by small mounds. The Octagon is connected to the Observatory Circle by a short walled enclosure. It also connects to Wright Square along a long, walled avenue. Directly to the south, the Great Hopewell Road to Chillicothe starts. The Octagon connects by a long avenue to the North Fork of the Licking River.

Small Circle: This circle is not on all maps. It is directly to the west of the terminus of the Great Hopewell Road and directly south of the Octagon. John Volker [Volker 2005] and others [Hively & Horn 1982] believe the Small Circle is important to the overall plan of Newark.

Observatory Circle (F), Octagon (Q), Great Hopewell Road (Z), Small Circle (T) [Salisbury & Salisbury 1862]

Wright Square: Only a few pieces survive. The square may have had eight entrance mounds but only four entrances and three, which are usually centered, are not. The square connects to the Octagon, the Cherry Valley Ellipse, and the Great Circle.

Cherry Valley Ellipse: A large mortuary complex containing some 12 mounds. [Lepper 2023] Destroyed. Connected by an avenue to Wright Square. Another avenue goes to the South Fork of the Licking River.

Salisbury Square: Also destroyed. Not connected to any other earthwork and across the river on another open plain. Hively and Horn believe that it is part of the site. [Hively & Horn 2013] The square has only two entrances and no entrance mounds. Attached to a small circle with an inner ditch.

Wright Square (B), Cherry Valley Ellipse (C), Salisbury Square (SS) [Salisbury & Salisbury 1862]

Great Circle: Around 1200 ft in diameter with an inner ditch that probably held water. The land slopes down, the walls go from 7 to 14' at a single large gateway. The walls are arranged such that they look the same height from the inside. At the center is an oval mound with lobes on each side, Hence the name, Eagle Mound. This was originally a large wooden building, called a Great House, which contained a hearth but no human remains. this Great House has been burned down and a mound built over it. The Great Circle connects to the Wright Square. [Lepper 2016]

Great Circle (A) [Salisbury & Salisbury 1862]

Basic topology of Newark. The main earthworks are confined by three rivers. There is an entrance from each. Salisbury Square is on a separate terrace, any other features have been lost. Logic suggests that the structure was linked to the Licking River to the north. Letter labels are from Salisbury and Salisbury. [Fig. 1 Author]

In 2005, John Volker took a class at Ohio State University from Bradley Lepper. Volker wrote a paper for the course about the geometry of the Newark Earthworks. Volker tried to get the paper published but it was rejected. Lepper passed a copy on to whoever was interested. I have reformatted the pdf file to be searchable and am providing a downloadable link with permission from the author.

Possible relationships between geometric elements at Newark [Volker 2005 Figure 3]

The circumference of the Great Circle is equal to the perimeter of Wright Square.

The area of Observatory Circle is equal to the area of Wright Square.

The square that circumscribes Observatory Circle has the same area as the Great Circle. The side of this square is the diameter of the Observatory Circle.

The area of the Octagon is twice the combined area of the Observatory Circle, and the walled avenue connecting the Observatory Circle and the Octagon.

Volker’s important addition is to show how ratios of small numbers can be used as a substitute for irrational numbers. I believe his discovery of a simple ratio of 4/5ths for ‘circling the square’ is unique. In [Geometry] I showed that these were associated with sets of rational approximations. I also added two more to the list: an approximation for √2 and squares and circles with equal perimeter/circumference. Marshall adds another ratio of 8/9ths for double-walled circles. The Great Circle can be thought of as a double circle where the ‘inner wall’ is a water feature. These approximations differ in the accuracy of their initial values and the slope of the line as sets of values converge. Also, whether the irrational represents a linear or a planar measure makes a difference. All of these need to be taken into account if a statistical model of these relationships is to be constructed.

Newark is one of the largest and probably the most complex geometric site. Once other sites are added the heterogeneity of the earthworks becomes apparent. Both within-site and between-site similarities have been proposed. Marshall claims that parts of different sites are affine transformations (translation, rotation, and scaling) of others. [Marshall 1987] Again whether these are true or archaeologically useful needs to be tested.

The earthworks can be looked at in two ways:

A set of planar shapes:

Circle

Square

Octagon

Ellipse

Rectangle

Triangle

These shapes can be combined in many ways and many cases overlap. There is some subjectivity here and it doesn't have anything to do with how the shapes were originally constructed but is a pure geometric decomposition. This leads to a set of topological relationships:

Category | Example | Commutative |

contained | A is contained in B | No |

overlaps | A overlaps B | Yes |

touches | A touches B | Yes |

connected | A is connected to B | Yes |

Notice that in one case the order in which the objects combine matters, sometimes not. This requires that all combinations of relationships be used, thus each category will have two binary numbers.

Shapes have measurements, a circle has a center, a diameter, an area, and a circumference. Likewise, a square has a diagonal, a center, an area, and a perimeter. Overlap and distance between connected shapes can be measured. Measurements can be compared: how one shape is related to another and whether there is any commonality in the size of shapes. Circles can be measured as to their circularity as squares can be measured as to their squareness. Sometimes the difference between a rectangle and a square is not possible when sides or parts of sides are missing. Then I will term the structure 'squarish' The following is a list of possible measured relationships:

Perfection of shape

Equal area

Equal perimeter/circumference

Inscribed (side-to-diagonal)

Circumscribed (diagonal-to-diagonal)

Inner Ring

A set of linear and non-linear walls:

Most walls can be segmented by a measure of curvature, a straight wall segment having zero curvature.

Walls are either connected directly or connected by gaps or gateways.

Walls have a length.

Gateways are another categorical type. They can be internal, leading to different regions inside the enclosure, or external, leading outside. These gateways control the flow of people within. Some gateways have mounds just inside. These mounds don't have burials. This does two things:

It divides people into two groups. For the individual, this can result in a choice, go right or left, or it can impose a choice, for instance dividing male and female.

It hides what is going on inside the enclosure until an individual is fully inside

A third type of gateway [McCord 2006] contains an enclosed space like a lobby one enters before entering the larger space. This hides the inner enclosure and restricts entrance.

Gateways and gateway mounds like the earthworks themselves are very heterogeneous.

There are other non-geometric details:

Whether there were posts used to outline the shape. A method of construction that is still an open topic.

construction materials

different colored clays

artifacts found in the earthworks fill

features, mounds, and artifacts found inside the structure

The Core

What is called the 'Core' is a region around the confluence of the Scioto River and Paint Creek. This region is at the southern boundary of the last Wisconsin glaciation and the beginning of the Appalachian Highlands. Both waterways form broad valleys before the Scioto narrows and flows south to the Ohio River. The Scioto flows in the remnants of an ancient large river, the Teays, which flowed north instead of south. The wide valley around Chillicothe is the remains of that river. Currently, the Ross County, Ohio town of Chillicothe sits in and among an extraordinary collection of earthworks and burial mounds. In the early 1700s, Chillicothe was a Shaunee village. After colonization, it was Ohio's first capital.

Chillicothe in 1847 [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate II]

Five earthworks in the Core have similar geometric features. These are a large circle, a smaller circle, and a large square. Also, all of each geometry is the same size throughout the five. These three features are called tripartite. Chris Carr and Susan Smyth suggest that this represents a tree-way alliance between peoples living in the three river valleys of the Scioto River, Paint Creek, and the North Fork of Paint Creek. [Carr & Smyth 2020]

Tripartite earthworks near Chillicothe, Ohio [Bernardini 2004, fig. 5, p. 337]

Mark Seeman and Kevin Nolan created a Bayesian model using all the dates from six sites in Ohio, two of which are tripartite. They concluded that Seip and Liberty were built about the same time and Seip was in use longer. [Seeman & Nolan 2023]

Tripartite earthworks Bernardini 2004, fig. 6, p. 337]

Notice that all five earthworks are arranged differently. Liberty and Works East include a smaller fourth circle and have the most similarity in shape. The distance between the large square and the small circle gets larger, the series is: Baum, Liberty, Works East, Seip, and Frankfort. This could mean nothing, or it could be how they fit into the landscape. Wesley Bernardini's paper is mainly an energetic analysis of construction of the five earthworks. He concludes that it took 150 to 400 workers 10 years to build each earthwork. [Bernardini 2004]

I will go into detail about five works in the Core, three in the Scioto Valley, and two along Paint Creek. This includes four of the five tripartite works, Frankfort works is under the town of Frankfort, Ohio. This is just scratching the surface but the five are representative and interesting.

Scioto River

High Banks Work and Turpen Tract [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate XVI]

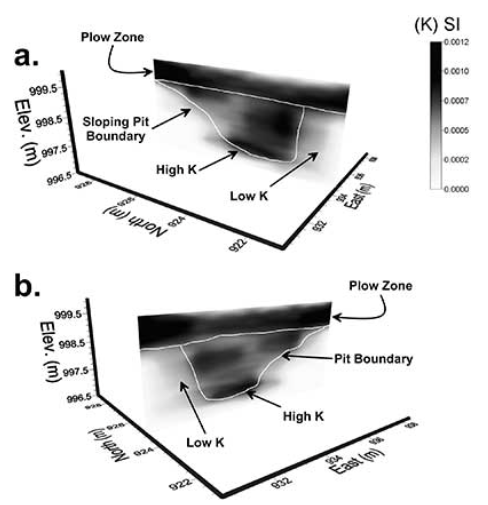

High Banks has a special relationship with Newark because it is believed to be one end of the Great Hopewell Road. [Schwarz 2016] This and other relationships I will come back to. [Landscape] In addition, it contains the only other octagon found so far in Ohio. Unlike Newark, the various major elements of the site are only loosely connected. Jarrod Burks divides the site into two parts, the upper large circle, and the octagon with a small circle on the side, and all the rest which he calls the 'Turpen Tract.' At the time of this writing, I am unable to find a copy of his results from the Turpen Tract. [Burks 2013b] His geomagnetic data on the top part of the site gives several new results:

Magnetic Anomalies [Burks 2013a, p. 47. fig 2.8]

There is a slight bulging in the large circle.

A second small gap in the large circle does not exist. Burks speculates that this was not a gap but a deliberately built low section of the embankment that by the time of Squier and Davis had worn away enough to look like a gap.

The second circle in Squier and Davis either doesn't exist, is located outside of the survey grid, or could be two much smaller anomalies and perhaps a very small circle.

Near the center of both the large circle and the octagon, there could be some sort of structure or structures.

A structure may exist north of the large circle.

For the octagon, four of Hively & Horns' measurements are slightly off. A diagonal line that bisects the large circle, a small parallel gateway, and the octagon is claimed by Hively & Horn to be exactly twice the diameter of the large circle. The revised figures change this but it is still within 1.3%

[Burks 2013a] The result is that earthworks show up easily in magnetic data even when the original structures have been almost flattened, which is important for finding new sites.

Liberty Works [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate XX]

Liberty Works contains some 14 mounds, the largest of which was first excavated by Squier & Davis in 1847. Diggings were done by 'local schoolboys,' by Frederick W. Putnam (1885), Warren K. Moorehead (1897), and William C. Mills (1907, 1903). In 1976-1977 it was excavated by a team directed by N'omi Greber of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. [Burks & Greber 2009] Named 'Edwin Harness Mound' after the landowner. It is located inside the larger circle and unlike the mound inside of the Great Circle at Newark, many graves have been found. Greber uncovered an elaborate post-hole pattern that once held up a large structure that she called a 'Big House.' At one time, this structure was dismantled and perhaps burned and the mound was built over it. [Greber 1983]

"The recent salvage work at Edwin Harness has added to our knowledge of Hopewell symbols. The classes we have found include numbers, directions, colors, shapes, opposition or binary contrasts, special trees and plants, and special uses of fire or smoke. These symbols reflect a system of thought and a way of life. One can find examples of the meaning of each of these within historic Eastern Woodlands peoples in their range of activities; gathering, hunting, gardening, curing, giving birth, giving names, marrying, praying, trading, achieving great deeds, and dying. They are part of the oral traditions which explain the origins of the world and of important cultural elements." [Greber 1983, p 92]

Structural post-hole pattern for the Big House at Harness Mound [Greber 1983, p. 28, fig. 3.2]

I have been looking through Hopewell artwork trying to see a connection between it and the various shapes and configurations of the earthworks. So far, this has been futile. Here you see the same general pattern of connected geometric shapes. This image is where Marshall gets the idea of a measurement standard and a laid-out grid as a general cultural standard for construction. [Marshal 1987] A large post-hole circle has been found inside Fort Ancient [Riodan 2020] [Burks 2014] and at one time an embankment is believed to have been built over it. I don't know if any other grid patterns have been found. In [Geometry] I talk about how the grid pattern was perhaps important to the conceptualization of the structures, but not necessarily their construction.

Works East [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate XXI No. 3]

Works East lies under the city of Chillicothe, Ohio, and the 1847 Squier and Davis' map is the only known image. It is important because of the orientation relationship with High Bank and Liberty that Hively & Horn have proposed. [Hively & Horn 2020] More about this in the next article [Sky]

Paint Creek

Baum Works [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate XXI No. 1]

The main attention to Baum Works was to a later Fort Ancient Culture village built on the site. [Skinner et. al 1981] Marshall between 1966 and 1984, surveyed the site. [Marshal 1987] Like in the Scioto River Valley, Hively & Horn have proposed an orientation relationship with Seip Works.[Hively & Horn 2020] [Sky]

Seip Works [Squier & Davis, 1847, Plate XXI No. 2]

Seip works contain several mounds with burials, two of them very large. Because of this, it has a long history of excavation starting in 1902. N'omi Greber took the post-hole pattern of the Harness Mound, rotated it 90 degrees, and placed it over the larger Seip mound.

Post hole pattern from Harness Mound rotated 90 degrees and placed over Seip Mound [Greber 1983, p. 88, fig. 10.1]

It can be seen that the post-hole pattern fits quite closely. Whether Marshall's idea of cryptographic overlays came from Greber or Greber's overlay idea came from Marshall is unknown.

In 2015 a site-wide geophysical survey was done at Seip in areas inside and outside the earthworks. The large circle has an elaborate entranceway, and both large mounds have oval embankments around them. In addition, they found many smaller features including the outlines of buildings. They found three types of geometric shapes:

Squircles (squares with rounded corners)

Perfect circles, shaped by ditches

Concentric post circles [Komp & Luth 2020 p. 71]

In addition, they found evidence of continued use of the earthworks grounds well beyond the Hopewell period.

Map of structures found during geomagnetic survey [Komp & Luth 2020 p. 61, fig. 4]

Close-up of the gateway at Seip. [Komp & Luth 2020 p. 61, fig. 4]

Small enclosures found in and around Seip [Komp & Luth 2020 p.87, fig. 7]

I've talked about the mathematics of squircles in [Geometry]. These are not squares with corners rounded by circles but a part of a continuum between a square and a circle or a rectangle and an ellipse. This fascination with the relationships and transformations between circles and squares carries into the building of structures of all types and sizes. The five works I mentioned here are just a small sample of the Scioto Paint Creek Core which includes two large burial complexes and many more earthworks. With modern methods, even the most destroyed can sometimes yield new secrets.

The rest of Ohio

The richness and extent of native settlement in Ohio is astounding. The long history of post-contact erasure is equally astounding and it has only been in the last couple of decades that this erasure may be starting to slow down and perhaps reverse. During the late 1800s, several large maps were made of the known earthworks. In 1914, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society published the Archaeological Atlas of Ohio in which each county has a separate map. The atlas terms both mounds and embankments earthworks and categorizes them into mounds and enclosures. The atlas contains around 587 enclosures and 3, 513 mounds. Estimates of what may have existed are as high as 10,000 mounds and 1,500 enclosures. In addition, the map contains contact-era native villages along with major land trails and rock shelters. [Mills 1914]

Earthworks in Ohio [Mills 1914, p. XI]

The map above shows a great concentration running through the Scioto River Valley, a concentration around Newark, east towards a major flint resource at Flint Ridge, and another in the salt region of Licking County. Notice that there are fewer as one goes north.

Satellite imagery along with LIDAR, ground penetrating radar, and geomagnetic imaging has transformed archaeology as erased earthworks and a whole new world of structures have been uncovered. These new technologies combined and visualized through GIS have sparked and encouraged grassroots support for preservation. Starting in 2016, the state of Ohio has been producing and releasing whole-state LIDAR imagery of better and better accuracy. [Ohio Geographically Referenced Information Program 2024] In 2023 it released imagery using a stronger laser that can penetrate thick stands of wood. Some farm woodlots have never seen the plow and some structures, especially on hilltops, might still be hidden in dense woods. In 2016 a former Archaeologist, David Lamp started looking at old aerial photographs from the 1950s. He found a couple dozen possible candidates for earthworks. One was at Blacklick Metro Park in Columbus. He contacted Jarrod Burks who did a geomagnetic survey of the park. he found a 10-foot diameter circle ringed by a ditch. [Ferenchik 2017] In 2016 Burks discovered a large post circle at a site called Heckelman in Erie County, near the lake [Burks 2017] It is unclear what the relationship is between post circles and circular embankments, but there is some evidence at Fort Ancient that an embankment was built over the post circle and the embankment was later removed. There is no evidence of posts in other geometric shapes. [Riodan 2020] Heckelman is one of the furthest northern sites in Ohio although I ran into rumors of earthworks at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River at Cleveland. [Brose 1974] [Peskin 2011] [Whittlesey 1871] Fieldwork by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in 2019 confirmed the circle and uncovered many other features. Some Middle Woodland artifacts were found along with later ones. Radiocarbon dating gave confounding dates in both the Middle and Late Woodland periods. This could be an example of continuous use over the centuries but it could also mean that some form of circle ceremonialism may have lasted much longer than realized. [Redmond 2019]

Extensive earthworks existed on the Ohio River at Cincinnati and along the Little Miami and Great Miami Rivers. Many have been lost but extensive hilltop enclosures like Fort Ancient still exist. In 2019 a hilltop enclosure called Fortified Hill was purchased by the Archaeological Conservancy and saved from development [Bowdoin 2019]

At Marietta, Ohio at the confluence of the Muskingum River and the Ohio River, the earthworks were built around an older Adena burial mound which still exists inside a cemetery. The mound has an embankment and ditch ringing the mound with one side open as an entrance. The relationship between the Adena and Hopewell cultures is still a mystery yet evidence points to Hopewell being a later expression of a mother Adena. The Washington County Library now sits on what was once a large mound. In 1990 N'omi Greber showed that this mound is a platform mound, a feature found in the south but the first verified in Ohio. [Greber & Pickard 1990]

At Portsmouth, Ohio, where the Scioto River empties into the Ohio River, a large earthworks complex sprawls across both banks of the Ohio into Kentucky. Of the many aspects of this complex, only one is large geometric, called Old Fort Earthworks in Kentucky, a square made up of six segments. On the Kentucky side is also an Adena-type mound, like in Marietta. [Uldrich 2019] All of the features are connected by banked parallel earthen walls, which also connect to the rivers. One section is over a mile long. Five miles up the Scioto River is Tremper, a mortuary complex surrounded by an oval enclosure. In the center of the enclosure is a large irregular mound covering a decommissioned Great House which was used to process the dead. I found a rumor about another 'Road' between Tremper and Portsmouth. I can't find much about it. Many beautiful animal effigy pipes were found at Tremper and in the Portsmouth region. These are made of a substance called 'pipestone.' Pipestone is found in this area but this pipestone comes from Illinois. Except for the lack of large geometries, Portsmouth reminds me of Newark, a great expanse of different elements connected between each other and the surrounding rivers by embanked pathways. The mound at Tremper looks vaguely like an animal, similar to the Eagle Mound in the Great Circle at Newark. Both hold Great Houses. Whether they are effigies or not is open for debate, effigies of this type come later in Woodland history. [Feight 2024]

Square in Kentucky across the Ohio River [Squier & Davis 1847, plate XXVIII No. 2]

Artist's conception of Tremper. [Stranahan 2024]

Earthwork ditches are still under the plow zone. They tend to hold water longer than the surrounding dirt. In the early summer during periods of low rain, this shows up as greener crops conforming to the shape of the ditch. In 2012, Google released imagery of Central Ohio taken in June during a dry season. Two possible sites were discovered, both along the Scioto River. One in northern Ross county and the other in Pickaway County south of Circleville. The Pickaway County site has been confirmed by Jarrod Burks. Named Jones Group, it consists of two ditch and embankment enclosures and a possible square. [Burks 2015b]

Jones Group [Burks 2015b, fig. 5, p. 5]

Further north and on the west side of the Scioto River across from Ohio State University is the Holder-Wright property in Dublin, Ohio. Holder-Wright colonial settlement dates back to the early 1800s and was recently sold to the city of Dublin to be used as a historic park. A map from 1894 shows two ditch and embankment circles with an unique rectangular ditch and embankment. Burks team found one circle and the rectangle and perhaps an edge of the second circle. [Burks et al. 2015a]

Holder-Wright earthworks [Burks et al. 2015a, fig. 2.16, p. 30]

Squier & Davis showed many circles and squares. Circles come in all sizes with lots of smaller circles, they showed few small squares or rectangles. What geomagnetic imagery has shown is that many of the smaller features drawn by Squier and Davis were wrong, both in shape and sometimes location. [Burks & Cook 2011] One possible reason is that were worn down and hard to recognize, even in 1847. This could be the fact that these features were not as high and possibly easier to plow. Another possibility is that they are older, thus more worn down. The graph below shows the size distribution in the area of the results from two earthworks. Notice a big jump in size at one point.

Size distribution of small enclosures [Burks & Cook 2011, Fig. 10]

A list of possible parameters include:

Area

The ratio of the major and minor axes

The thickness of the base

The size of the opening

The type of the opening

Inner ditch, outer ditch, or no ditch

Is there a mound inside? Type?

The table above shows a survey of shape types. The first two columns show a survey done by William S. Webb in 1941. [Webb 1941] The second two columns show the additional new results from three works. Notice more categories of shapes and more rectangles. This table is from 2010 and Burks has had many more years of geophysical surveys.

The Periphery

The Early and Middle Woodland periods were dominated by two cultural expressions called Adena and Hopewell. Both created what is called an 'interaction sphere', where flows of raw and processed materials, ideas, and practices bound together a large portion of Eastern North America. That these two may of been different expressions of the same culture is still an open question. The later Hopewell expression is believed to have affected a much larger portion of the continent. How do we know this? Raw material sources can be traced. Obsidian from Yellowstone and the Great Smokey Mts, meteorites from western Kansas, copper from Northern Lake Superior, silver from upper Ontario, shells from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, flint from Flint Ridge in Ohio, and many other locations. Artifacts and evidence of practices show up all over. Sometimes these can be traced back directly to Ohio, sometimes they are local expressions of an Ohio style. In this case, these people are also named 'Hopewell.' This is a purely arbitrary name. There must have been a constant movement of people spreading goods and ideas. This could be through trade, pilgrimages, spiritual quests, proselytizing, or migration. In addition, each artifact type has its pathway of distribution.

Copper-wrapped pan pipes believed to be associated with Moon Goddess worship show one pathway. [Cree 1992] Another is female clay figurines. Over 150 were found at the Mann site in Indiana, near Cincinnati. Others were found at Temper and perhaps Marietta. They have been found all along the Gulf Coast, from Mobile Bay, Alabama to Northwest Florida. The culture around Mobile Bay has been given a Hopewell name, Porter Hopewell because of their similarities to the Ohio culture. [Walthal 1975] Whether these were manufactured in the South or came from Ohio is unknown but Mann is believed to be a major manufacturing site for many items. [Indiana State Museum Mann Site Figurines] These figurines could also represent a bride exchange as these women would be highly regarded for their esoteric and practical knowledge. Earthworks cannot be transported, but geometric ideas, structure, and even building instructions can be packaged in a story or song and travel long distances. [Memory] The local culture must not only have the skills to implement these ideas but also the human labor and will to do so.

West Virginia

West Virginia has many mounds, especially where the state borders the Ohio River. There is even a town called Moundsville in the Northern Panhandle. Upriver from Marietta is a place called Ben's Run that was supposed to once have earthworks but they no longer exist. [Riggs & Riggs 1927] I found nothing else on the Web except pop archaeology tales of mothmen and skeletons of giants. Within Moundsville is Grave Creek Mound, one of the largest found in the United States. [Wikipedia Grave Creek Mound] It is believed to be Adena. A map in the West Virginia Archaeologist, 1950 No. 3 shows 220 different sites in West Virginia. [Norona 1950, no. 3] These include villages and rock shelters, along with mounds. Brad Lepper sent me a picture of a hexagonal outline of an earthwork from Moundsville. [Lepper private communication] I believe it is originally from issue no. 4 of the West Virginia Archaeologist but I was unable to obtain a copy. [Norona 1950, no. 4] Hexagon shapes are rare, with only two in Ohio, so this may be an important find if it can be verified.

[Lepper personal correspondence]

Kentucky

I have noticed in my research how each state or region within each state has its archaeological flavor, a period, or a culture that dominates the interests and resources of the state. Large earthworks called Hopewell exist on the Ohio River opposite the earthworks at Portsmouth, Ohio. Another was found in southwestern Kentucky along the Mississippi River. It is another partial square with a long avenue much like the one opposite Portsmouth.

15FU37 or Tuning Fork [Mainfort & Carstens 1987, p. 58, fig. 1]

Marshall surveyed two sites in Mason County, Kentucky called Fox Farm Site and Dover Mound, which I cannot find. [Marshal 1987] Many small circles or squircle-type enclosures exist but are termed 'Adena' even though they do not contain burials like similar circles (squircles) called 'Hopewell' in Ohio. Supposedly many Hopewell-type hilltop enclosures exist in the state that have never been studied. [Manzano & Shields 2012]

The word 'Adena' came from the name of the estate in Chillicothe of Thomas Worthington, an Ohio Senator and Governor. The large mound on the property is now called Adena Mound. A study in 2014 took C14 dates from fiber and bark found in the central grave during a 1911 excavation and now stored in an Ohio History Connection collection. These dates are near the end of a range of C14 dates for Adena sites and could be within a few generations to a few hundred years before the Hopewell site of Mound City. These dates belong to the lowest and thus the earliest burials. The mound had two stages of construction with no dates currently for the second stage. This suggests a continuous culture with perhaps no overlap and a short hiatus in between. [Lepper et al. 2014]

In Kentucky, these categories seem to break down. [Pollack 2008] Edward R. Henry proposes renaming Adena / Hopewell as Middle Woodland Ceremonialism. [Henry 2020a] His point is that these categories mask the extreme local diversity of how this ceremonialism is carried out, plus they get in the way of any attempt to discover the defining ideas, the similarities occurring over a vast landscape and a vast period of time.

Mt Horeb Complex is a set of sites in Lafayette County, Kentucky that have been categorized as Adena. These include two irregular earthworks misnamed Peter Village and Grimes Village. Peter Village was first surveyed in 1820 by the French naturalist Constantine Rafenisque. He was an eccentric genius who by 1820 was ostracized by the American scientific community who refused to publish him. Besides naming hundreds of plants and animals he was the first to suggest that Indigenous Americans came to this continent over a land bridge from Siberia. He also stated an early version of the theory of evolution which Darwin acknowledged in the third version of Origen in 1861. Squire and Davis used his map of Peter Village but not his description.

"Plan for Peter Village as drawing by Constantine Rafenisque, ca.1820 (original in the collections of M. J. King Library, the University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky)" [Clay 1985, p. 2, fig. 1]

Peter Village is not a village but a ceremonial enclosure, roughly a twenty-sided polygon. The site location had been lost until it was first excavated in 1983 by R. Berle Clay. This was considered an unusual structure for Adena at the time as it was large, contained no mound or mortuary evidence, was not a perfect circle, and contained an outside ditch instead of an inside one. Clay found a row of post holes following the ditch, some 4,000. [Clay 1985] [Polluck 2008]

LeBus Circle is part of the Mt Horeb complex. It is a nearly perfect circle with an inner ditch and no mound inside the ditch. The image below shows a feature labeled: 'Interior Circular Anomaly.' This feature turns out to be a pit containing a spring. The second image below shows the interior structure of the pit, and how it slopes down towards the spring source. Springs can be ephemeral and the lowering of the water table over the last two hundred years has changed the hydrology along with the landscape. I know that there are models for finding locations of active springs but I don't know of any model that can extrapolate back in time. One scenario proposed is that these circles were built to mark and preserve sacred places in the landscape, These could be special rocks, trees, plants, springs, caves, landscape views, astronomical sitings, visions, and historical events. These places had names and the structures built on them were built for specific reasons. [Discover Kentucky Archaeology. LeBus Circle, 2022] [Henry 2011]

15Ck10 is a burial mound site in Clark County in central Kentucky. It has an outside enclosure and an inner ditch. The mound is not conical but has three lobes. This mound has never been physically disturbed. Edward R. Henry used strictly non-evasive techniques to study, so as not to disturb the human remains. These include: [Henry, et. al 2014]

magnetometry

electromagnetic induction (EM)

ground-penetrating radar (GPR)

electrical resistivity tomography (ERT)

downhole magnetic susceptibility (DMS) - this is mildly invasive and was not done in any location where the other technologies showed human remains to exist.

The study also tried to use the results of this study in a regional anthropological framework. 15CK10 lies between an eastern Kentucky region of mounds and a central Kentucky one. Each region contains mounds using different mortuary practices. This study finds two mortuary traditions, multiple double post circular rings outside the enclosure, and multiple construction periods. They see it as a transition point between two regional sets of customs. Here is their conclusion:

"By considering our site-based interpretations of 15Ck10 within the larger models of Adena interaction we try to further discussions of complexity, mobility and social change. The mobility of people on the eastern and central Bluegrass Adena landscape brought with it the exchange of ideologies and perspectives on mortuary ritual. The intersection of various perspectives on Adena ritual practice can be seen in the construction of 15Ck10. This mound’s possible composition of both central and eastern Bluegrass ceremonial and mortuary traits suggest that it was a locale where people interacted and influenced one another, altering the mortuary ideology represented at the site through time." [Henry, et. al 2014, p. 25]

Winchester Farm is located between Pike Village and the main Mt. Horeb mounds. It is a small non-circular enclosure with an inner ditch and no inner mound. In addition, a double post enclosure was built inside the ditch. In 2021, Henry, et. al released a study of the site. They extracted a large variety of plant and faunal remains, and artifacts, and conducted an extensive geological analysis of soils at different horizons. [Henry, et. al 2021] The biological samples allowed them to obtain 17 C(14) dates from the site. Since dating accuracy relies on a 95% confidence interval this means that on average 1 out of 20 dates could be incorrect. This makes 17 a sweet spot. They then used Bayesian chronological modeling [Ramsey 2024] to generate a biography of the whole site. [Hamilton & Krus 2018] This process creates a set of probabilistic models that can be tested against other data to describe possible biographical scenarios. Bayesian modeling has been critiqued as 'subjective' and 'unscientific' but it is a model of how humans think.

Archaeological restatement of Bayes Rule [Hamilton & Krus 2018, p.190, eq. 3]

Process of Bayesian chronological modeling [Hamilton & Krus 2018, p.193, fig. 2.2]

The study suggests the following sequence of events:

The site was used extensively long before anything was built on it

The ditch was built first, then fill from the ditch was used to create the embankment

The embankment was removed and part of it was burned and thrown back into the ditch

A double post enclosure was built that has no entrance, thus sealing off the site from use

Whether the ditch filled up through erosion or deliberate action is unknown

Additionally, the embankment and ditch are in the shape of a 'squircle.'

Winchester Farm squircle [Henry, et. al 2021, p. 5, fig. 4]

Several other sites have meaning within the Middle Woodland ceremonial context:

Evans site in Montgomery County, Kentucky. Yellow clay was used as a platform to place bodies on. In Ohio, yellow clay was used to cap the tops of earthworks.[Discover Kentucky Archaeology, Evans 2024]

Bullock Mound is in Woodford County Kentucky. It is unclear whether there was a ring and ditch enclosure. Under the mound is a rectangular double post shape which might have held up a Great House-type structure, like in Ohio. [Discover Kentucky Archaeology, Bullock 2024]

In North Carolina near the Tennessee border, in a region called the 'Appalachian Summit', Alice Wright has excavated a site called Garden Creek with two squircle-type enclosures and several mounds. The enclosures are of a rare type because they may be just ditches with no embankment. Only one enclosure was excavated. The site was previously occupied, and then the ditch was dug. Various artifacts were produced using mica and quartz, and artifacts of a distinctive Ohio style occurred within the enclosure. The ditch was filled with layers of various colored soil, and then a post ring was built surrounding the enclosure. Later the posts were removed and the post holes were filled with river rocks. Another site like this has been found a few miles away. [Wright 2019]

I found only two Hopewell-type large geometric enclosures in Kentucky both containing squares. However, the central Kentucky Adena landscape has various elements, motifs are perhaps a better term, that play out in Ohio within the larger Hopewell sphere.

H. Berle Clay is an archaeologist who studies the earlier 'Adena' period. Writing in 1987 he defines two types of enclosure, a large vaguely ellipsoid earthwork with an outside ditch and a smaller circular enclosure with a gateway and an inside ditch. Inside, it was either empty, contained a work area, or had a conical burial mound. Graves Creek in West Virginia has just a ditch around it. Recent technological breakthroughs have discovered another shape, the rounded square or 'squircle.' He also found post circle enclosures inside the circle and ditch and at Mt Horeb, he found post circles that didn't conform to the earthwork which meant that they were earlier. Like many places, this is evidence of long-term usage of the site. [Clay 1987]

Gary Wright discusses the use of water features and their relationship to enclosures. Small circular enclosures (some are now considered squircular) in particular. He uses A. Martin Bryers' structural naming convention. He expands to other water features found, springs and what looks to be dug wells, the lakes at Newark, and the placement of these sites partially surrounded by rivers and streams. Of interest is the idea that the walled passageways and roads might of been an abstract representation of a waterway. This is all combined with ethnographic information, Turtle Island, and the Earth Diver stories. [Wright 1990]

Alice P. Wright studies Middle Woodland cultures in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. In 2020 she published a book about one site she has been studying called Garden Creek. At an earlier symposium, she mentioned the influence of Byers' structural ideas. [Wright 2012] Her book is dense with data and ideas. For a period of time, the people who lived here built two enclosures by building a ditch. Within these enclosures, they manufactured goods made out of mica and quartz, goods that have been found in Ohio. Thus they actively participated in the cultural expression that is called Hopewell. In addition, their enclosures contained the structural elements of enclosures found all over the Woodlands. This suggests a transmission of not only manufacturing knowledge but also knowledge of construction techniques. Wright includes in her book a database of small enclosures throughout the Woodlands, each having seven structural attributes she calls 'architectural morphemes.' [Wright 2020]

Presence and Absence

Wright's morphemes contain three binary attributes, called Presence/Absence data. This term comes from ecological studies of species ranges. A region is broken up into a grid and if a certain species is present in the grid during a count then the grid is given a value of 1, else 0. This method has its downside because an absence can mean many things, it could mean that an animal wasn't present at this time or that the grid square was inaccessible. Binary data is computationally easy so a model having this type of data can have more dimensions. Binary data within a hierarchy also has problems. For instance, if x = 1 then y can be 1 or 0 but if x = 0 then y is Null. With archaeological data, even Presence can be suspect. If all one knows about a site is from a 180-year-old map that shows a circular embankment with an interior ditch, does this mean we are 100% sure that this enclosure exists? Presence/Absence data is best represented as a probability. With geomagnetic data, an embankment usually appears as a 'halo' on one side of the ditch. If no halo was seen, does this mean that there was no embankment? Maybe, the odds are better, and with more evidence, they will get better still.

Mid South

Old Stone Fort is in South Central Tennessee. It is not a fort but a Middle Woodland hilltop enclosure, the furthest south I have found. It contains no mounds but has an interesting alcove type of entranceway. [Wikipedia Old Stone Fort]

Old Stone Fort [Thruston 1896, p. 253, fig. 1]

Pinson Mounds is a large ceremonial site in Tennessee. Pinson is known for the number, variety, and size of its mounds including conical and platform mounds. As explained in [Geometry] a 1917 map showing extensive embankments around both a central mound group and another around the whole site is probably inaccurate. The eastern mound group does have a partially circular enclosure. [Mainfort et al. 2011]

The Johnson site is 6 km northwest of Pinson on the same South Fork of the Forked Deer River. Like Pinson, it was described by William Myer of the Smithsonian Institution and a map was produced by E. G. Buck, a local civil engineer in 1917.

Original 1917 map of the Johnson Site, Tennessee. [Henry, et. al 2020b, p. 4, fig. 2]

The map shows a long embanked avenue running north from the largest mound to another smaller one. To the south are three smaller mounds connected by paths or causeways. In 2020 Edward R. Henry and colleagues published a study of the site using multiple sensory approaches. [Henry, et. al 2020b] This was accompanied by a suite of GIS analyses of the LIDAR DEM data especially created for archaeology called the Relief Visualization Toolkit. [Kokalj & Somrak 1998] [Kokalj & Zakšek n.d.] [Zakšek et al. 2011] These include the following functions:

hillshading

hillshading from multiple directions

PCA of hillshading

slope gradient

simple local relief model

anisotropic sky-view factor

positive and negative openness

sky illumination

local dominance

The idea is that these different analytical methods can be composited into maps that will bring out hidden archaeological features. The major mounds were found and the north-south embanked avenue, However, the three small mounds to the south and their connecting paths were not. We now know that Meyer tended to embellish his maps. The 1917 map does not have the distortion of Buck's Pinson map. The Johnson site is considered a precursor to Pinson yet contains an architectural element of a walled avenue that reappears throughout the middle Woodlands.

The Marksville site is located in central Louisiana. It consists of mounds, two nongeometric enclosures, and perhaps as many as 50 small enclosed circles. These circles have a ditch on the outside and a single entrance. The inside is unique as it is a dugout basin with a deep pit in the center An intense fire burned in the pit. The pit was cleaned out over the years and eventually covered with the old ashes. [McGimsey 2003]

1928 map of the Marksville site [McGimsey 2003, fig. 2, p. 49]

McGimsey states that these circles are unique because of their small diameter, an outside rather than an inside ditch, and the inside basin and pit. Since they are unique they cannot be related to any other Middle Woodland structure. They may be unique but variety is everywhere, they are still an expression, a repatterning of basic motifs in local form. To see where the size falls in a range of sizes. I took three data sets, [McGimsey 2003] [Burks & Cook 2011] [Webb 1941] Webb is considered Adena, Burks & Cook is considered Hopewell, and McGimsey is Marksville. I plotted them in the chart below. The y-axis shows the area in meters squared. The McGimsey data does fall at the low end but there is a Webb outlier and it overlaps the Burks & Cook data. The high end of Burks & Cook overlaps Webb. Note that the Webb and the Burks & Cook data are not raw.

Chart 1 [Author]

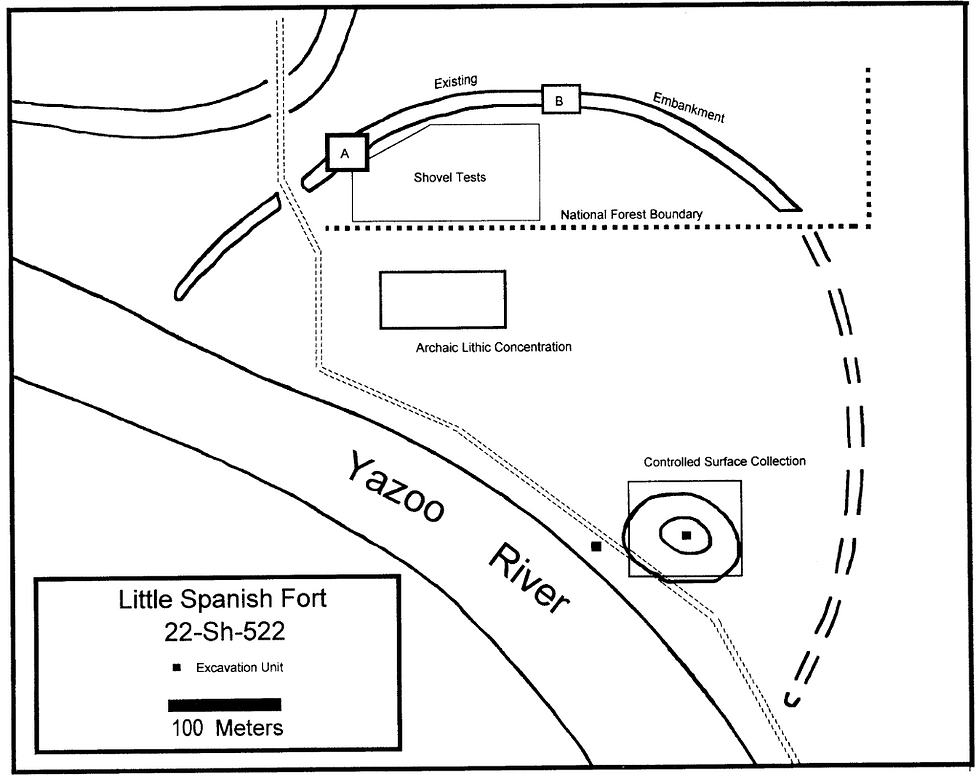

Three sites in the lower Yazoo Basin of Mississippi contain semi-circular embankments. These are:

Spanish Fort

Little Spanish Fort

Leist

The sites may be much older and related to Poverty Point but the embankments are currently considered Middle Woodland. [Jackson 1998]

Little Spanish Fort [Jackson 1998, fig. 2, p. 204]

Florida

Middle Woodland artifacts and mounds extend all through the state but works seem to be confined to South Florida, especially in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. A post circle was found near Miami in 1998. The posts were set in square holes cut into limestone.

Lake Okeechobee supported an advanced civilization that built extensive well-engineered canals to the Gulf of Mexico in the west. This area had activity from around 1000 B.C.E. to colonial times. There has been continual speculation that the area had Olmec and later Mayan contacts. Although this could be possible, no artifacts have been found. There is proof of contact with Ohio in the form of Flint Ridge blades. One problem with contact with the South is how the Gulf Stream Current forms a barrier around South Florida, Native peoples settled in Cuba. They even journeyed as far north as the Bahamas but there is no evidence that they ever came to Florida. [Seidemann 2001]

An extensive collection of mounds and earthworks is centered around the appropriately misnamed 'Fort Center.' James Marshall surveyed four of these sites between 1981 and 1984. In 1998, William Gray Johnson published a study in which he categorized the various types and formed a chronology of these types. He mentions linear embankments called 'ridges', circles, squares/rectangles, and two types of 'circular-linear' earthworks. These are semi-circles, often with a mound inside, with a linear avenue leading out from them. [Johnson 1998] Two recent studies by Nathan R. Lawres and Mathew H. Colvin have shown, using C14 dating that the earthworks tested and some of the mounds all fall within the Middle Woodland range and that Johnson typology does not match the chronology he suggested. This study is at sites called Big Mound City and Big Gopher Mound, which are just two locations in a larger landscape. [Lawres & Colvin 2017] [Lawres & Colvin 2021]

1963 aerial photograph of Tony's Mound (Belle Glade Culture) showing complex circular and linear features [Florida Public Archaeology Network 2021]

Fort Center site contains four circles. It must be noted that these are not embankments or embankments with an inner or outer ditch, but a ditch only. Also, the circle's diameter is close to the diameter of the Newark Great Circle and the outer circle at Circleville. There are no C14 dates for either of these sites but for the Fort Center circle there are two dates, 800 - 350 B. C. E. and 300 to 210 B. C. E. Dates for some of the sites in the Core and around Cincinnati give a Hopewell period in Ohio of 90 - 120 C.E. to 395-430 C. E. [Seeman & Nolan 2023] This suggests that the Fort Center circle predates the large earthworks in Ohio. There is part of a larger circle that seems to be concentric to the inner one and part of a smaller circle inside that does not look concentric. [Thompson & Pluckhahn 2012]

Fort Center is also supposed to contain squares and/or rectangles but I can find nothing about them.

Fort Center Circles. The black dot at the upper left is some artifact of the digitization. [Thompson & Pluckhahn 2012, p. 56, fig. 4]

The division of the history of around 1/3rd of North America into convenient periods can be useful but can also get in the way. Earthworks including mounds and embankments can be traced back to Poverty Point, Louisiana around 1700 B.C.E. to 1100 B.C.E. Six semi-circular concentric embankments enclose a central 'plaza' where 36 overlapping post-hole circles of various sizes have been found. These are believed to be ceremonial and not part of a structure. Some overlap the embankments so they could be earlier or later constructions. The site includes some of the earliest pottery in the woodlands plus the source of an earlier expression of female figurines that also spread across the Gulf Coast. [Walthall 1975] Poverty Point is considered one of the first cities in North America. [Hargrave et al. 2021]

Poverty Point timber circles [Hargrave et al. 2021, fig. 4 p. 199]

Mound building in the Southeast may go back as much as 2,000 more years with sites like Denton, Mississippi. [Connaway et al. 1977] At the moment, timber circles found at Poverty Point are the oldest, but they are being discovered thanks to new technology. Other early circles are circular rings composed of shells that are found all along the Gulf and Atlantic coast. These have been dated all through the middle and late Archaic. [Schwandron 2010]

Various shell rings [Kassabaum 2019, p. 221, fig. 6]

Shell ring in southern Florida [Schwadron 2010, p. 129, fig. 6.10]

Indiana

The Mann Site is in extreme SW Indiana on the Ohio River near the confluence of the Wabash River. The site has one square, two partially squarish shapes, and several small circles. Mann is part of a much larger region that includes mounds small circles or squircles and several villages. The site contains extensive pottery from Louisiana and Georgia and is a major manufacturing and distribution center for artwork and implements.

Mann Site [Strezewski 2024, Posey County, fig. 1]

Bertsch, New Castle, and Anderson are located in east central Indiana. The sites contain a mixture of Adena and Hopewell styles. All three sites contain a large circle, a panduriform (a violin shape), and many small enclosures. Bertsch has 25 small enclosures, mostly squircles. Some of these are arranged in a large circular pattern. [Davis & Burks 2020]

Anderson, New Castile, and Bertsch [Davis & Burks 2020, p. 31, fig. 6]

The Fudge Works and the Graves Enclosure are east of the Anderson complex and about 13 miles apart. Both have squarish enclosures with rounded corners containing a single mound. Fudge has two entrances, one with an alcove - a small squarish enclosure with an inner ditch. Adena and Hopewell artifacts have been found. In one wall of the large enclosure, they found the upside-down impression of a basket used to haul soil. Unfortunately, McCord does not provide a picture or drawing of the pattern. [McCord 2006]

Fudge Works and Graves Enclosure [Davis & Burks 2020, fig. 5, p. 18]

Outline of Fudge Works [McCord 2006, fig. 28, p. 59]

Again a heterogenous mixture of forms around three different cultural expressions. There is still a sharing of motifs, large squarish shapes, and many small semi-geometric ones. The squares at Fudge Works and Graves enclosure are unique in that they have only two entrances, the one at Fudge consisting of a secondary small structure. McCord speculates that Fudge might be a ball court related to the Southwest but the dates don't line up, the earliest Hohokum ballcourts being around 750 C.E. In addition, there is no evidence, Hohokum ballcourts had plastered floors and some even had centerlines. [Archaeology Southwest 2024] This doesn't mean there might have been some organized competitive activity within some of these enclosures, just that there is no evidence.

Illinois

The Illinois expression of Middle Woodland ceremonialism was centered along the lower portion of the Illinois River. Villages and ceremonial sites have been found, both containing mounds with burials. Villages are situated on upper river terraces with long linear mounds while the ceremonial sites were situated on lower terraces and contained conical mounds. There is one large irregular enclosure at Golden Eagle Earthworks near where the Illinois River enters the Mississippi. It contains one entrance and an outer ditch. At least one mound in the region at a place called Ogden-Fettie Mounds is enclosed with an embankment. The ring around the mound is termed 'geometric' and a 'pentagon' but I don't see it. It is unclear about any ditch. Some mounds were filled with layers of different colored dirt, some had alternate basketfuls of different colored dirt [Charles 2012] and others contained 'bricks' of cut sod that were turned upside down and stacked. It is believed that this sod came from deliberately fashioned prairies where in parts of the forest the trees were felled and repeated burnings allowed grassland to take root. [Van Nest et al. 2001] Because of the quality of artifacts in the region, it was believed that people from here settled in Ohio DNA evidence from burials has shown just the opposite, groups from Ohio settled in Illinois. [Bolnick & Smith 2007]

Golden Eagle Enclosure [Ward et al. 2015, fig. 2]

Lower Illinois Valley mound types [Herrmann et al. 2014 fig. 1, p. 166]

Enclosure F197 Ogden-Fettie mounds [Martin 2013, fig. 5, p. 18]

Iowa

West of the Mississippi there is confusion with dating earthworks as there is a continuation of the Middle Woodland mound and earthwork building into the Late Woodland by a culture called Oneota. Most of the Middle Woodland sites are found in Southeastern Iowa. I was drawn to Iowa by the possibility of two octagons. An early drawing by Newhall in 1841 near the Toolseboro Mounds shows an eight-sided earthwork made out of semi-circles, a very unique shape.

1841 drawing of earthworks [Riley & Tiffany 2014, fig. 2, p. 145]

Unfortunately, a LIDAR study has shown a circular structure with a mound inside, not close to the 1841 drawing. There is evidence for two more of these but from what I can see they don't look like Newhall's map.

Circular enclosure found with LIDAR [Riley & Tiffany 2014, fig. 6a, p. 148]

At a site called Gass Farm, LIDAR picked up light soil in a field, another possible octagon. Again, a later magnetometer scan of the area came up with nothing. So far, the only confirmed octagons are in Ohio.

A possible octagon at Gass Farm [Whittaker & Green 2010, fig. 5b, p. 37]

Gass Farm has a hilltop enclosure consisting of two ditch and earthwork rows but no walls along the dropoff. Just beyond one wall are two springs and a large hole that seems to be an access to the springs.

Ditch and earthwork hilltop enclosure. Springs are two circles SW of the southern earthwork. [Whittaker & Green 2010, fig. 7, p. 40]